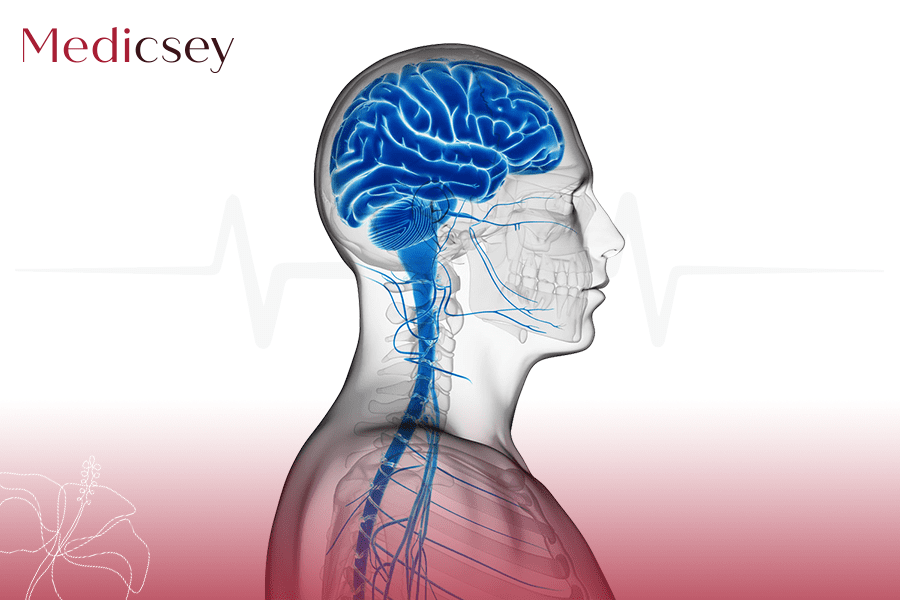

Epilepsy is one of the most common and disabling neurologic conditions, yet we have an incomplete understanding of the detailed pathophysiology or treatment rationale for much of epilepsy.

A “seizure” is a paroxysmal alteration of neurologic function caused by the excessive, hypersynchronous discharge of neurons in the brain. “Epileptic seizure” is used to distinguish a seizure caused by abnormal neuronal firing from a nonepileptic event, such as a psychogenic seizure. “Epilepsy” is the condition of recurrent, unprovoked seizures. Epilepsy has numerous causes, each reflecting underlying brain dysfunction (Shorvon et al. 2011). A seizure provoked by a reversible insult (e.g., fever, hypoglycemia) does not fall under the definition of epilepsy because it is a short-lived secondary condition, not a chronic state.

“Epilepsy syndrome” refers to a group of clinical characteristics that consistently occur together, with similar seizure type(s), age of onset, EEG findings, triggering factors, genetics, natural history, prognosis, and response to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). The nonspecific term “seizure disorder” should be avoided.

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurologic conditions, with an incidence of approximately 50 new cases per year per 100,000 population (Hauser and Hersdorffer 1990). About 1% of the population suffers from epilepsy, and about one-third of patients have refractory epilepsy (i.e., seizures not controlled by two or more appropriately chosen antiepileptic medications or other therapies). Approximately 75% of epilepsy begins during childhood, reflecting the heightened susceptibility of the developing brain to seizures.

CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURES AND EPILEPSIES

Seizures are divided into three categories: generalized, focal (formerly called partial), and epileptic spasms. Focal seizures originate in neuronal networks limited to part of one cerebral hemisphere. Generalized seizures begin in bilateral distributed neuronal networks. A seizure can begin focally and later generalize. Seizures can originate in the cortex or in subcortical structures. Using a detailed history, EEG findings, and ancillary information, a physician can often categorize the seizure/epilepsy type, after which an appropriate diagnostic evaluation and treatment plan is formulated.

The main subtypes of generalized seizures are absence, generalized tonic–clonic (GTC), myoclonic, and atonic (Table 1). Absence seizures (formerly called petit mal) involve staring with unresponsiveness to external verbal stimuli, sometimes with eye blinking or head nodding. GTC seizures (formerly called grand mal) consist of bilateral symmetric convulsive movements (stiffening followed by jerking) of all limbs with impairment of consciousness. Myoclonic seizures consist of sudden, brief (“lightning-fast”) movements that are not associated with any obvious disturbance of consciousness. These brief involuntary muscle contractions may affect one or several muscles; therefore, myoclonic seizures can be generalized or focal. Atonic seizures involve the loss of body tone, often resulting in a head drop or fall.

Anything that disrupts the brain’s natural circuitry can bring on this disorder:

* Genes

* A change in the structure of your brain

* Severe head injury

* Brain infection or disease

* Stroke

* Lack of oxygen

Most people with epilepsy never find a specific cause.

Anti-seizure drugs are the most common epilepsy treatment. If a medication doesn’t work, your doctor may adjust the dose or prescribe a different drug for you. About two-thirds of people with the brain disorder become seizure-free by taking their meds as prescribed.

.png?locale=fr)